ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL

PERCEPTIONS OF UNIVERSITY STUDENTS ON GENDER EQUALITY. A REVIEW FROM ITS SOCIOCULTURAL CONTEXT

PERCEPCIONES DE ESTUDIANTES UNIVERSITARIOS SOBRE LA EQUIDAD DE GÉNERO. UNA REVISIÓN DESDE SU CONTEXTO SOCIOCULTURAL

PERCEPÇÕES DE UNIVERSITÁRIOS SOBRE IGUALDADE DE GÊNERO. UMA REVISÃO DE SEU CONTEXTO SOCIOCULTURAL

Puriq

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Huanta, Perú

ISSN: 2664-4029

ISSN-e: 2707-3602

Periodicity: Continua

vol. 5, e521, 2023

Received: 11 August 2023

Accepted: 19 October 2023

Published: 25 October 2023

Corresponding author: lguerrero@upmh.edu.mx

CITE AS: Guerrero-Azpeitia, L. A. (2023). Percepciones de estudiantes universitarios sobre la equidad de gé-nero. Una revisión desde su contexto sociocultural. Puriq, 5, e521. https://doi.org/10.37073/puriq.5.521

Abstract: The objective was to explore the perceptions that university students express regarding gender equality based on their sociocultural context. Some elements of Bourdieu’s sociological perspective were recovered, in order to approach said object of study as a production of subjectivity from the objective conditions of the students. Methodologically, a questionnaire was designed with the intention of recovering elements of the students’ sociocultural context and at the same time exploring their perceptions of the gender perspective; Data treatment was performed through multiple correspondence analysis. The main results highlight the relationship between the social conditions of the students, such as the schooling of their parents and their economic activity, and their perceptions of gender equity. Finally, it can be concluded the importance of family sociocultural conditions in shaping the perceptions and opinions of university students.

Keywords: Gender equality, subjectivity, sociocultural context, University students.

Resumen: El objetivo fue explorar las percepciones que, sobre la equidad de género, manifiestan estudiantes universitarios en función de su contexto sociocultural. Se recuperaron algunos elementos de la perspectiva sociológica de Bourdieu, a fin de abordar dicho objeto de estudio como una producción de subjetividad a partir de las condiciones objetivas de los estudiantes. Metodológicamente, se diseñó un cuestionario con intención de recuperar elementos del contexto sociocultural de los estudiantes y al mismo tiempo explorar sus percepciones sobre la perspectiva de género; el tratamiento de los datos se realizó a través del análisis de correspondencias múltiples. Los principales resultados destacan la relación entre las condiciones sociales de los estudiantes —escolaridad de los padres y su actividad económica, por ejemplo— y sus percepciones sobre la equidad de género. Finalmente, se puede concluir la importancia de las condiciones socioculturales familiares en la conformación de las percepciones y opiniones de los estudiantes universitarios.

Palabras clave: Equidad de género, subjetividad, contexto sociocultural, estudiantes universitarios.

Resumo: The objective was to explore the perceptions that university students express regarding gender equality based on their sociocultural context. Some elements of Bourdieu’s sociological perspective were recovered, in order to approach said object of study as a production of subjectivity from the objective conditions of the students. Methodologically, a questionnaire was designed with the intention of recovering elements of the students’ sociocultural context and at the same time exploring their perceptions of the gender perspective; Data treatment was performed through multiple correspondence analysis. The main results highlight the relationship between the social conditions of the students, such as the schooling of their parents and their economic activity, and their perceptions of gender equity. Finally, it can be concluded the importance of family sociocultural conditions in shaping the perceptions and opinions of university students.

Palavras-chave: Igualdade de gênero, subjetividade, contexto sociocultural, estudantes universitarios.

INTRODUCTION

Gender equity, as an object of study, can be approached from different approaches and currents of thought, ranging from psychological studies to those of a sociological nature, obviously with their different nuances, it can also be approached from cultural, political and economic studies [focus on the university environment].

The importance of including the principle of equality in the university environment is considered as a way to achieve high levels of academic quality, which in turn will influence the construction of a more equitable society; however, the way to achieve this is precisely the training processes of the teaching staff (López et. al, 2016). Although there are positive dispositions towards equality, situations of discrimination persist, such as social stereotypes, discriminatory language and favoritism both in university teaching and in the exercise of student leadership (Merma et. al, 2017), there is a clear need for actions aimed at raising awareness and preventing gender-based violence in the university environment (Calero and Molina, 2013).

In the domestic sphere, although there is an openness to share household activities, it is the woman who assumes a leading role in the development of household chores and childcare and, on the other hand, men have greater levels of freedom to develop activities traditionally classified as masculine and although, in the school environment the aforementioned differences are attenuated, it is the productive sector in which “careers” and “productive areas” for women and men are still present (Mendoza et. al., 2017). Additionally, it is known that economic growth is linked to the expansion of employment opportunities and access to higher income, it is linked to government policies mainly aimed at women starting from the fact that at the basis of human development is the principle of universality of the aspirations of society as a whole (Solis, 2016).

Regarding the assumptions of gender inequalities that are presented in university students are part of the hidden curriculum of educational institutions, where students internalize them from the construction of hypotheses and assumptions about them; this reproductionist perspective, the author continues, is not part of educational planning, but is a reflection of society (Dome, 2019). Although it should be mentioned that awareness is important but not enough, once students “say they have heard about gender inequality, however, there are many things to do, since the University is a great field of action to train and sensitize university students about gender inequality” (Rocha et. al, 2022, p. 75).

In addition, social representations allow understanding the subjectivities of social agents in a particular context, thus, university students construct concepts, feelings, perceptions and evaluations, but also the concern for achieving equality, however, they are reproducers of a cultural heritage, particularly in the category of gender (Dorantes et. al, 2023). In this sense, although it can be observed that there is an apparent equality among university students, there are indications that “men in traditional aspect, but women are not left behind either, since they are also a focus of resistance in masculinity attitudes” (González and Miranda, 2016).

However, not all university spaces have the same perception, a high perception of violence and gender inequality has been reported, which begin to evidence violent behaviors that in other times went unnoticed in various areas of university life, where one of the manifestations are “violent experiences arise from conditions not accepted by heteronormativity, commonly males try to verbally but indirectly assault through jokes or sarcastic comments towards women or homosexuals” (Medrano and Talamantes, 2016).

In any case, it is very common for gender equity to be considered as something subjective and for some researchers, such studies lack systematicity or even validity; for this reason, in the approach to reality presented here, it was decided to adopt some theoretical-conceptual elements of Bourdieu by making possible the study of subjectivity under the condition of incorporating the objective conditions that produce it. Thus, the research questions posed were: What ar’e the perceptions of university students regarding gender equity? How do socioeconomic and cultural factors influence the shaping of such perceptions? In order to answer these questions, this article is composed of the conceptual references necessary to construct both the data and the method, the analysis and discussion of the results, the preliminary conclusions, as well as the bibliographical references.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

With respect to the theoretical references recovered, Bourdieu establishes that social practice is the integration of two senses, the objective one attributed to the objective conditions and the subjective one associated with the sense of what is experienced by the agent. These meanings, recommends the author, can only be separated for analysis, but only on condition that they are integrated in the explanation and understanding of a given field or social space, so that any approach to reality that considers only any of the meanings will be, in any case, a partiality that will prevent conceiving them as a dialectical process, where the objective constitutes the subjective, but where the subjective also constitutes the objective. To account for the above Bourdieu establishes three concepts, among others that make up his theoretical approach, which are central to his sociological perspective: a) the field obviously associated with the objective sense, b) capital and c) habitus associated with the subjective sense or sense of what is experienced by social agents.

The field can be conceptualized as a network of objective relations between the positions occupied by social agents and whose origin is determined by both present and potential conditions (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 2005); capital, on the other hand, is conceived as accumulated labor and can be presented in a material, internalized or incorporated state (Bourdieu, 2001); finally, the habitus is a product of history and has to produce both individual and collective practices, thus reproducing past experiences that have been recorded as schemes of perception, thought and action (Bourdieu, 2007).

In this sense, and assuming that objective conditions are producers of subjectivity, but also under certain conditions, subjectivity produces objectivity, it has a dynamic and at the same time relational character. This makes possible the study of subjectivity, evidently from the social conditions that produce it, thus “the real is the relational: what exists in the social world are relationships. Not interactions between agents or inter-subjective ties between individuals, but objective relations” (Bourdieu and Wacquant, 2005, p. 150).

Thus, the social exists both in external and internal structures and there is an interdependence between them and schematically the formula of the practical sense is expressed in the following way: Field + [ habitus + capital] = social practice (Bourdieu, 1979, p. 99). Thus, for the author, there is a close relationship between the habitus or dispositions of the agents according to the position they occupy in the field and which is originated by their volume and structure of capital.

In addition, Castañeda (2009) considers that the study of the social agent requires an approach from different spheres such as the biological, cognitive, social and cultural; but also demands an integration both as a product and as a producer of a process that is in itself reproductive, thus keeping special relevance in the recovery of the bases in order to understand their own social practice.

In terms of gender equality, UNICEF considers that the sex-gender system can be understood as a social and cultural construction, but it is also a system of representation that assigns meanings and values to the people who make up a community normally by their sex and age. In this sense, it establishes a difference between sex and gender, attributing the first concept to the set of biological, anatomical and physiological characteristics that define human beings as male or female, while gender is understood as:

Set of social, cultural, political, psychological, legal, and economic characteristics that different societies assign to people in a differentiated manner as belonging to men or women. They are sociocultural constructions that vary throughout history and refer to the psychological and cultural traits and specificities that society attributes to what it considers “masculine” or “feminine. This attribution is concretized using, as privileged means, education, the use of language, the “ideal” of the heterosexual family, institutions and religion (UNICEF, 2017, p. 9).

In this way, the gender perspective seen as an analytical category (or in its case interpretative) in the social sciences, allows evidencing those spaces of inequity, injustice, inequality between men and women; who at birth have the same rights, however, are the characteristics derived from the androcentric culture which establish roles and stereotypes that condition, at least to some extent, the opportunities and also the differences for both genders (Camarena et. al, 2015).

Estrada, Mendieta and González (2016, Pp. 30-31) consider that “the process of political culture, the appropriation of habits, thoughts, traditions and in general the way of thinking around the roles that are established around gender, are a social construction”, the authors continue assuming that “the underlying assumption in gender inequality is the socio-cultural convenience of giving women a subordinate role to men, but also as a mecanism that is promoted from symbolic, material and social forms”. Finally, for Guerrero (2018) the study of the gender perspective in university level students requires the recovery of the objective conditions of the agents as producers of subjectivity, this with the intention of having a point of reference for the objectification of their perceptions, beyond the particular study of the concept of the gender perspective

The methodological strategy consisted of three clearly defined moments: 1) Characterization of the social and economic conditions; 2) Exploration of the perceptions of university students regarding gender equity and 3) construction of the sociocultural conditions of the agents and the corresponding perceptions based on multivariate analysis techniques.

To achieve the above, an instrument was designed in google forms with two sections, the first for the exploration and subsequent characterization of the social and economic conditions: school levels and occupation of parents, monthly income, objective educational and economic resources; the second section consisted of questions for the identification of perceptions on gender equity under a Likert scale modality. The instrument was applied to a total of 242 students of the Universidad Politécnica Metropolitana de Hidalgo (UPMH) of the educational program of Logistics and Transportation Engineering (ILT), the unit of analysis is located in central Mexico.

Regarding the construction of the data, multidimensional analysis was used as a reference, whose particularity is the concretion of both objective and subjective dimensions; specifically, the analysis of simple and multiple correspondences was adopted, whose main characteristic is to value the interdependence between variables or categories, facilitating their interpretation through the perceptual maps generated from the aforementioned interdependence (Hair et al., 1999). In particular, SPSS version 22 software was used to construct the perception diagrams by means of the multiple correspondence analysis technique.

RESULTS

The economic characteristics of the headquarters of the unit of analysis are mainly agriculture and livestock, it lacks industrial parks in its geographic delimitation, although it co-lines with two municipalities where an industrial park is installed and the Logistics Platform of Hidalgo (which, although it is projected to be an important logistics node, it is still in its initial stages of construction). As far as can be detected, the UPMH is not located in an area of high technological development.

The instrument was applied to a total of 242 students, 118 females (48.8%) and 124 males (51.2%) of Logistics and Transportation Engineering (ILT); with an average age of 20.33 years (standard deviation of 2.035). Of the total number of students surveyed, 20 do not live at home with their parents (7 women and 13 men), 38 only live with them on weekends or holidays (23 women and 15 men), while 184 live with their parents (88 women and 96 men); these data show that a slightly higher number of women are those who move from their homes to study, on the contrary, and in similar proportion, men do not need to move as much as women.

Regarding religion, Catholic is the most practiced religion with 79% of the cases, followed by Christianity with 7.1%, atheists with 6.2%, 7.7% practice other religions, it is worth mentioning that in the Catholic religion both men and women have the same percentage, women show a slight tendency towards Christianity and men towards other religions. In terms of monthly income (in Mexican pesos) 51% of households earn less than $5,000, 33.1% earn between $5,000 and $10,000, 12% earn between $10,000 and $20,000, and finally, 4.1% earn more than $20,000.

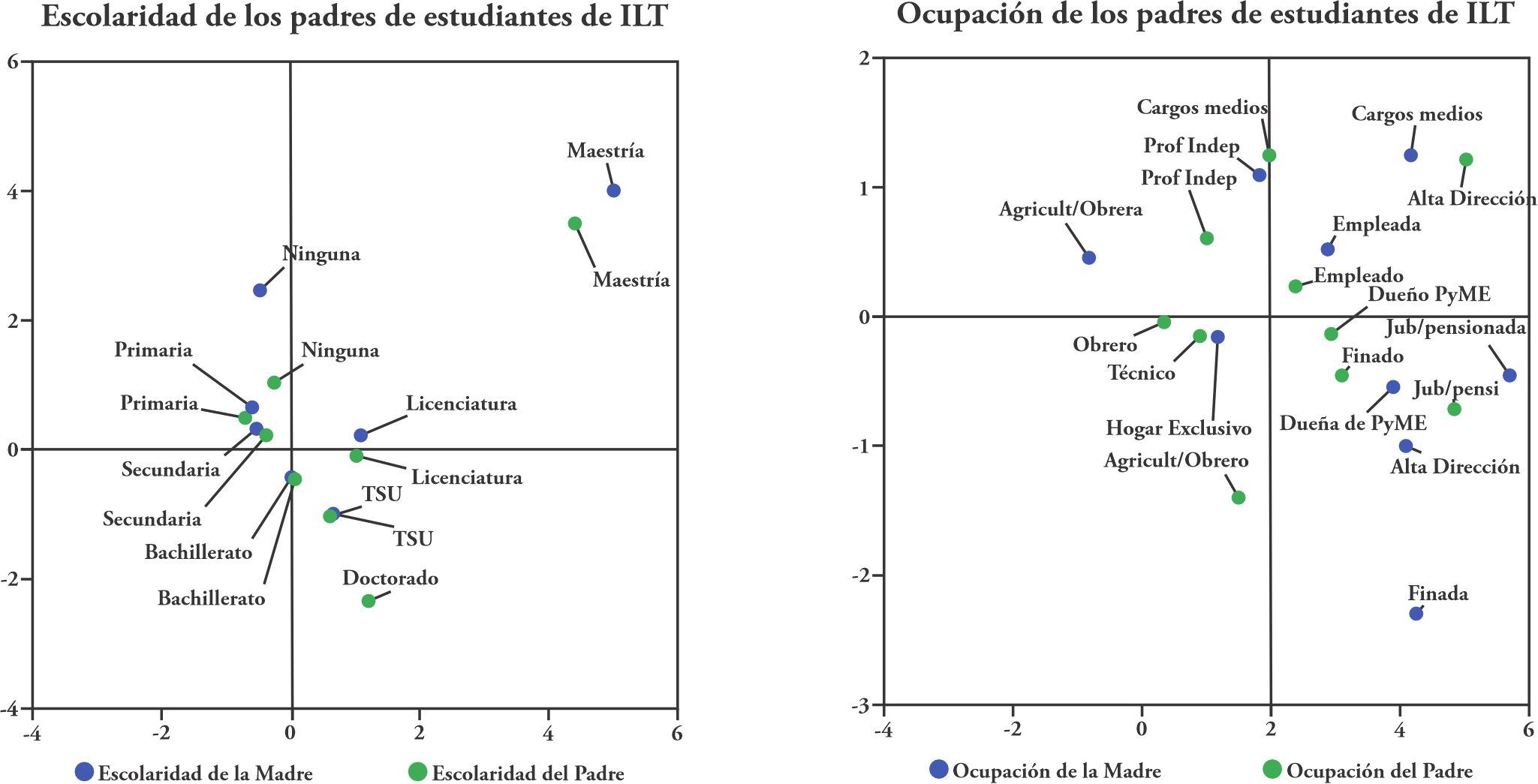

To construct the relationship between objective conditions and perceptions of gender equity, we first characterized the relationship between the level of schooling of both the mother and father of the students, and in a similar exercise, we did the same for the occupation of both parents. In this sense, and before showing these characterizations, it should be mentioned that, from the treatment of the data by means of the analysis of simple correspondences, a cumulative inertia of 0.705 was obtained up to the second dimension in the relationship referring to the schooling of the parents of the students surveyed, while for the relationship referring to their occupation there is a cumulative 0.735.

In figure 1, a close correspondence can be seen in the educational level of both parents, which is more evident when the schooling refers to basic level studies (primary, secondary) where it can be established that the parents of the students tend to form a family relationship without so much distinction in the educational level. In the case of those parents whose schooling is at a high school level (baccalaureate), university technician (TSU) or bachelor’s degree, they tend to form families with partners who have the same educational level; a much more evident situation in the case of both parents having master’s degrees. In this sense, it is noteworthy that of all the students, none of the mothers have the corresponding doctorate level studies; consequently, it is the men who have this educational level and there is a greater tendency for men to have established closer ties with women with TSU level and to a lesser extent with bachelor’s or bachelor’s degree levels.

In addition, the occupation of both parents does not correspond as closely as in the case of schooling, except when both parents are employees and, although partially, when both are independent professionals. In particular, it is observed that mothers who dedicate themselves exclusively to the home tend to form marriages with men who are technicians or workers; in the case of men who occupy high-level management positions, they tend to have as partners those women who hold middle-level positions; On the other hand, mothers who occupy senior management positions, who are owners of small and medium-sized enterprises (PyMES) or who are retired tend to have as partners husbands who are retired or deceased, and to a lesser extent those who are owners of PyMES.

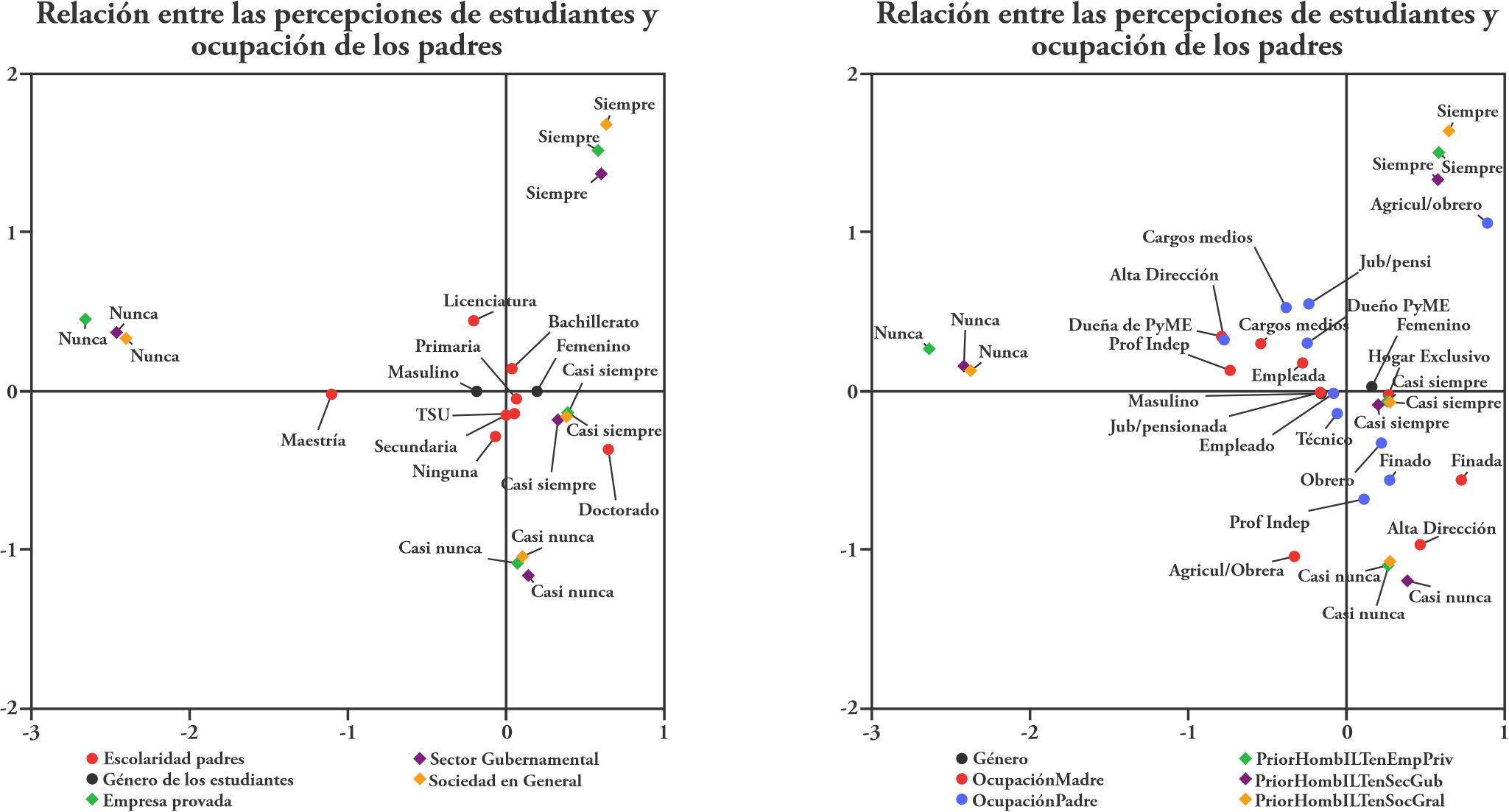

Regarding the elements of subjectivity such as the perceptions that men have of women in different areas of life, we have an average Cronbach’s alpha of 0.804 (0.839 for the horizontal dimension and 0.762 for the vertical dimension) and an inertia value of 0.629 (0.675 for the horizontal dimension and 0.584 for the vertical dimension) taking the parents’ schooling as a reference. Now, taking their occupation as a reference, the above indicators are for Cronbach’s alpha an average of 0.776 (0.805 for the horizontal dimension and 0.742 for the vertical dimension), as well as an inertia value of 0.527 (0.562 for the horizontal dimension and 0.492 for the vertical dimension). In set 2, it is possible to review the relation between students’ gender, their perceptions regarding preference toward men in different areas of professional and daily life and: 1) parents’ schooling (left diagram) and 2) parents’ occupation (right diagram).

Regarding the relationship between the students’ perceptions and the parents’ schooling, it can be observed that the answers present a high degree of concentration according to the Likert scale (always, almost always, almost never and never), that is, there is a clear tendency for the students to respond unanimously with relative independence of their gender; specifically, the answers “always” and “never” are farther away from the rest of the options. It is also observed that female students tend to consider that there are greater opportunities for men than for women in the areas of professional life in both the private and governmental sectors, as well as in society in general; these perceptions, although shared by the students, represent a slight difference with respect to the opinion of their female peers. On the other hand, there is no significant difference between the perceptions mentioned above and the academic level of the parents, except in the case of those students whose parents have master’s degrees, who tend to consider that there is not necessarily a greater preference for the male gender.

In addition, students whose fathers work as day laborers or laborers are those who consider that there is always a preference for men, while students whose mothers are exclusively engaged in household activities tend to consider that “almost always” there is a greater preference for men in the different areas of productive and social life; in contrast, when mothers are engaged in activities related to upper management or work as farmers and laborers, students tend to consider that “almost never” there is a preference for men. In addition, it is observed that, in the case of female students, there is a greater dispersion in their perceptions and the activities of their parents, although they are more likely to assume that “almost always” men have a greater preference.

Regarding the perception of whether women are more efficient in the performance of their functions than men in different areas of social life, such as the political, business, university and governmental spheres, it was identified that the perceptions in this regard are practically the same, obtaining an average Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.939 (0.952 and 0.926 for dimensions 1 and 2) in a multiple correspondence analysis with a reduction to two dimensions. However, with the intention of visualizing the results in percentages, the perceptions of both sexes for each of the scales are shown in Table 1, to the detriment of a perception diagram which, due to the characteristics of the results, would make visualization difficult because of the high concentration of the data (Mu = female, Ho = male, To = total).

Particularly in the case of politics, 42.4% of women agree that they perform better than men, but it is the men who express total agreement with this premise versus 13.5% of women; however, 8.1% totally disagree with this statement, compared to 6.8% of women. In relation to the business environment, similar tendencies are maintained, but there is a greater difference in that men totally agree that women perform better than men (21.7% of men versus 16.9% of women). In the case of the university environment, very similar percentages were identified, except that men express disagreement that women perform better, 33.9% versus 30.5% respectively. Finally, in the governmental sphere, it is noteworthy that men strongly agree that women perform better (15.3% versus 9.3%, respectively).

It can be identified that, with slight variations, perceptions are very similar between men and women. From the findings, it is highlighted that there is a perception that women have better performance in different areas of social life (agree and totally agree), particularly in the university and business spheres, and even men state that they totally agree that women perform better in politics, business and government, for example.

| Perceptions | Women’s improved performance by field (in percentages) | |||||||||||||

| Policy | Company | University | Governmental | |||||||||||

| Mu | Ho | To | Mu | Ho | To | Mu | Ho | To | Mu | Ho | To | |||

| Totally disagree | 6.8 | 8.1 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 6.5 | 6.7 | 8.5 | 5.6 | 7 | 9.3 | 8.9 | 9.1 | ||

| In disagreement | 37.3 | 34.7 | 36 | 32.2 | 37.1 | 34.7 | 30.5 | 33.9 | 32.2 | 34.7 | 37.1 | 36 | ||

| Agreed | 42.4 | 40.3 | 41.3 | 44.1 | 34.7 | 39.3 | 39 | 39.5 | 39.3 | 46.7 | 38.7 | 42.5 | ||

| Totally agree | 13.5 | 16.9 | 15.3 | 16.9 | 21.7 | 19.3 | 22 | 21 | 21.5 | 9.3 | 15.3 | 12.4 | ||

In addition, they were asked whether women should prioritize the family over personal development; in this aspect, it was the female students who most emphatically expressed their total disagreement, and although men share this position, they do so to a lesser extent than women. Regarding the hypothetical case that women should only form heterosexual families, even with minor differences, more women expressed total or partial disagreement with this premise, while men were more inclined to traditional relationships. Finally, with respect to the importance of the feminist movement, it is men who express a greater polarization (totally agree or disagree), practically doubling the statements of women, who express a more neutral position.

In particular, in the case that women should prioritize family over personal development, it is women who express total disagreement (55.9% compared to 31.5% of men), and it is also observed that men totally agree with this premise (15.3% versus 9.3% of women), which in some way suggests a position in men that could be considered traditionalist or “macho”. With respect to the fact that women should only form heterosexual families, again it is the men who express total agreement with this in a higher percentage (18.5% compared to 11% of women). Regarding the importance of the feminist movement, it is men who express their total agreement with 14.5% compared to 7.65% of women (For further references, see Table 2).

| Perceptions | Women must prioritize family over personal development | Women should only form heterosexual families | The feminist movement is important | ||||||||

| Mu | Ho | To | Mu | Ho | To | Mu | Ho | To | |||

| Totally disagree | 55.9 | 31.5 | 43.4 | 35.6 | 34.0 | 34.7 | 12.7 | 22.6 | 17.8 | ||

| In disagreement | 22 | 44.4 | 33.5 | 32.2 | 29.8 | 31.0 | 40.7 | 31.5 | 36 | ||

| Agreed | 12.7 | 8.9 | 10.7 | 21.2 | 17.7 | 19.4 | 39 | 31.5 | 35.1 | ||

| Totally agree | 9.3 | 15.3 | 12.4 | 11 | 18.5 | 14.9 | 7.6 | 14.5 | 11.2 | ||

Source: Own elaboration

DISCUSSION

From the analysis of the results, the relative relationship between the students’ perceptions and their parents’ level of schooling and occupation can be seen. This correspondence not only allowed us to outline some features of subjectivity, such as perceptions of gender equity in this case and some objective considerations of the students, but it also lays some foundations on which further research is needed in order to characterize the production of such subjectivity.

Under this consideration, the results presented here made it possible to answer the research questions posed and, at the same time, they raise new questions about the factors that trigger the social construction of the students’ perceptions of gender equity. The findings refer to the existence of a relationship, but do not facilitate the understanding and interpretation of the dispositions of the social agents in question, although they evince some features of the influence of sociocultural conditions on social practice.

It could be observed, for example, that there is a close relationship between the students’ dispositions and the parents’ schooling, as well as the profession or social work they develop, so that, according to the theoretical position adopted, the cultural and economic capitals of the families are playing a preponderant role in the students’ perceptions; however, being an exploratory study, it is necessary to keep a healthy distance between such statements and the weak understanding of the approach to the reality presented here.

To mitigate the above, it is recommended that subsequent studies include techniques for obtaining information that allow the identification of social practice and not only the perception of social agents, such as participant and non-participant observation, ethnography and focus groups, to mention just a few techniques.

CONCLUSIONS

The study of subjectivity manifested through perceptions, opinions, beliefs, emotions and feelings, among others, implies, among other considerations, recovering the objective conditions that produce them; in this way, the study of singularity demands the use of theoretical-methodological constructs that allow an approach to social reality with a greater degree of systematicity without pretending to reach levels of universality.

In some way, it is perceived that, for students of both sexes, there is a general perception that women perform better than men in various aspects of social life, although it should also be mentioned that there are traits of traditional attitudes regarding the role that women should play, Even women are the ones who have perceptions related to such positioning, such as prioritizing the family over their personal development or even a relatively low affinity for the feminist movement, perceptions that, according to the results, may have a basis in the religion practiced by social agents.

Although the use of multidimensional analysis techniques provides relevant construction elements, it is necessary to recover those that are typical of qualitative analysis, such as the semi-structured or in-depth interview, participant observation or even life history in order to identify whether such dispositions are indeed habitus on the one hand and, on the other, to know the capitals and the corresponding position occupied in the social space, as referred to in the selected theoretical approach.

Even with the above, the present study made it possible to demonstrate, at least in part, the importance of the sociocultural context in the perceptions of university students in relation to gender equity; the importance of such findings is based on the eventual social reproduction mediated in their social practices as university students, but also as members of society in a broader sense.

REFERENCES

Bourdieu, P. (1979). La distinción: Criterio y bases sociales del gusto [Distinction: Criteria and social bases of taste]. México: Taurus.

Bourdieu, P. (2001). Poder, derecho y clases sociales [Power, law and social classes]. Bilbao: Editorial Desclée de Brouwer S.A.

Bourdieu, P. & Wacquant, L. (2005). Una invitación a la sociología reflexiva [An invitation to reflective sociology]. México D.F.: Siglo XXI editores.

Bourdieu, P. (2007). El sentido práctico [The practical sense]. Argentina: Siglo XXI Editores.

Calero, M.A. & Molina, M. (2013). Percepción de la violencia de género en el entorno universitario. El caso del alumnado de la Universidad de Lleida [Perception of gender violence in the university environment. The case of students at the University of Lleida]. Catalunia: Edicions Universitat de Lleida.

Castañeda, A. (2009). Trayectorias, experiencias y subjetivaciones en la formación permanente de profesores de educación básica [Trajectories, experiences and subjectivations in the continuing education of basic education teachers]. México: UPN.

Camarena, M., Saavedra, M. y Ducloux, D. (2015). Panorama del género en México: situación actual [Overview of gender in Mexico: current situation]. Revista Científica Guillermo de Ockham, 13(2), 77-87. http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1053/105344265008.pdf

Dome, C. (2019). Percepciones de estudiantes sobre desigualdad de género en la Universidad. Un estudio exploratorio. XI Congreso Internacional de Investigación y Práctica Profesional en Psicología. XXVI Jornadas de Investigación. XV Encuentro de Investigadores en Psicología del MERCOSUR. I Encuentro de Investigación de Terapia Ocupacional. I Encuentro de Musicoterapia [Student perceptions of gender inequality at university. An exploratory study. XI International Congress of Research and Professional Practice in Psychology. XXVI Research Conference. XV Meeting of Researchers in Psychology of MERCOSUR. I Meeting of Occupational Therapy Research. I Meeting of Music Therapy]. Facultad de Psicología - Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires. https://www.aacademica.org/000-111/785

Dorantes, J., Martínez, K. & Hernández, R. (2023). Las representaciones sociales sobre la categoría de género. Una mirada estudiantil universitaria [Social representations on the category of gender. A university student perspective]. Revista de Investigación y Evaluación Educativa, 10(1), 108-131. https://doi.org/10.47554/revie.vol10.num1.2023.pp108-131

Estrada, J., Mendienta, A. & González, B. (2016). Perspectiva de género en México: Análisis de los obstáculos y limitaciones [Gender Perspective in Mexico: Analysis of Obstacles and Limitations]. Opción, 32(13), 12-36. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=31048483002

López, I., Viana, M. & Sánchez, B. (2016). La equidad de género en el ámbito universitario: ¿un reto resuelto? [Gender equity in the university environment: a challenge solved?]. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de formación del profesorado, 19(2). 349-362. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/reifop.19.2.211531

Mendoza, I., Sanhueza, S. & Friz, M. (2017). Percepciones de equidad e igualdad de género en estudiantes de pedagogía [Perceptions of gender equity and equality in student teachers]. Papeles de Trabajo, (34), 59-78. chrome-extension: http://www.scielo.org.ar/pdf/paptra/n34/n34a05.pdf

Medrano, L.A. & Talamantes, J. (2016). Género, masculinidad y violencia. Percepciones en el entorno universitario [Gender, masculinity and violence. Perceptions in the university environment]. En D.I. Valdez, R. Valenzuela & E. Ochoa (Comp.), Igualdad de Género: Investigaciones (pp. 66-74). Sonora: ITSON

González, F. & Miranda, J.J. (2016). Manifestaciones sobre la violencia entre estudiantes de nivel superior. Justificaciones desde la masculinidad. En D.I. Valdez, R. Valenzuela & E. Ochoa (Comp.), Igualdad de Género [Manifestations of violence among high school students. Justifications from masculinity. In D.I. Valdez, R. Valenzuela & E. Ochoa (Comp.), Igualdad de Género]. Investigaciones (pp. 66-74). Sonora: ITSON

Guerrero, L. (2018). Gender perspective in university students. A review of your perceptions and academic trajectories [Gender perspective in university students. A review of your perceptions and academic trajectories]. Journal-Health Education and Welfare, 2(3), 1-8. https://www.rinoe.org/bolivia/Journal_Health_Education_and_Welfare/vol2num3/Journal_Health_Education_and_Welfare_V2_N3_1.pdf

Hair, J., Anderson, R., Tathan, R. & Black, W. (1999). Análisis multivariante (5ª Ed)[ Multivariate Analysis (5th Ed.)]. Madrid: Prentice Hall Iberia.

Merma, G., Ávalos, M.A. & Martínez, M.A. (2017). Percepciones del alumnado y de los y las líderes estudiantiles sobre inequidades de género en la universidad [Perceptions of students and student leaders on gender inequalities at the university]. Reencuentro: Género y Educación Superior, (74), 59-80. https://reencuentro.xoc.uam.mx/index.php/reencuentro/article/download/931/926/

Rocha, M., Mendoza, L. & Sevilla, J. (2022). Percepciones de equidad de género y su relación con la estructura familiar de los estudiantes: Caso Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas [Perceptions of gender equity and its relationship with the family structure of students: Case of the Autonomous University of Tamaulipas]. Revista DYCS Victoria, 4(1), 67-76. https://doi.org/10.29059/rdycsv.v4i1.145

Solís, S. (2016). Igualdad de género: una condición del desarrollo humano [Gender equality: a condition for human development]. Trabajo social UNAM, (10), 11-24. https://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/ents/issue/view/4366

UNICEF (2017). Perspectiva de Género. Comunicación, infancia y adolescencia, guía para periodistas [Gender Perspective. Communication, childhood and adolescence, a guide for journalists].

Author notes

lguerrero@upmh.edu.mx

Additional information

ORCID:

Luis Arturo Guerrero-Azpeitia: Universidad Politécnica

Metropolitana de Hidalgo, Hidalgo, México.

Luis Arturo Guerrero-Azpeitia: Universidad Politécnica

Metropolitana de Hidalgo, Hidalgo, México.

AUTHORS’

CONTRIBUTION:

Luis Arturo Guerrero-Azpeitia: Conceptualización, Curación de datos, Análisis formal,

Adquisición de fondos, Metodología, Investigación, Administración de proyectos,

Recursos, Software, Supervisión, Validación, Visualización, Redacción: borrador

original, Redacción: revisión y edición.

FUNDING:

Funding for this research was

provided by the author.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

The author declares that he has no

conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

:

The collaboration of university

authorities and students for the development of this research is gratefully

acknowledged.

REVISION

PROCESS:

This

study has been reviewed by external peers in double-blind modality.

Revirso A:  Marilú Farfán-Latorre, mfarfan@unamad.edu.pe

Marilú Farfán-Latorre, mfarfan@unamad.edu.pe

Revisor

B: Anonym.

EDITOR RESPONSABLE:

José Héctor Livia Segovia, jlivia@unfv.edu.pe

José Héctor Livia Segovia, jlivia@unfv.edu.pe

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

:

Not applicable.